Almost all Chinese speakers know the famous “Thirty-Six Stratagems” and many apply these strategies or practical ruses in warfare, politics, business, gaming, and even daily life. But no one knows for sure when the book was written and who the author was.

Many historians and scholars believe that the term “thirty-six stratagems” was first used in the biography of Tan Daoji (?-436 AD), a renowned general of the State of Song (420-479 AD) during the Southern Dynasty (420-589 AD) and that the book was compiled during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

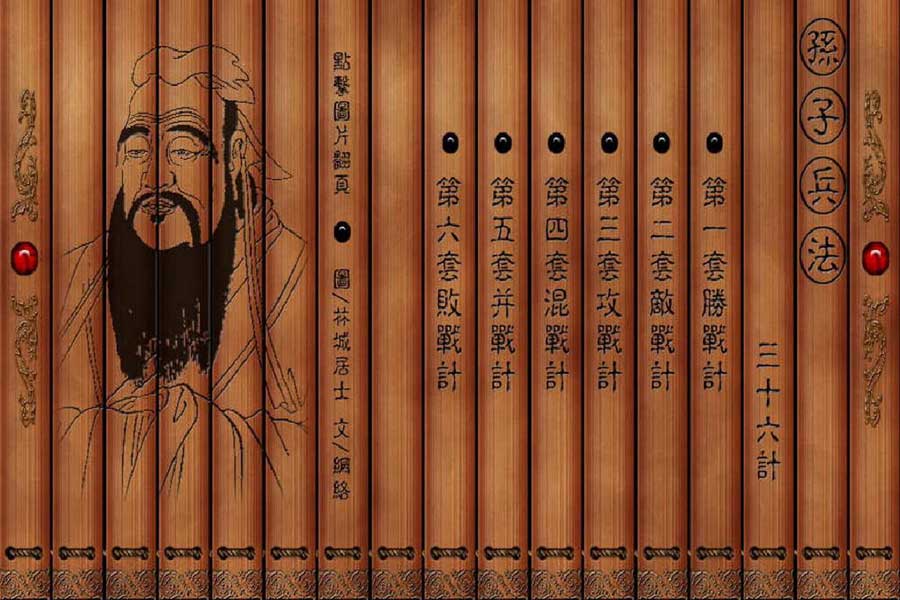

The book is divided into six chapters, with each chapter consisting of six stratagems:

- Chapter 1: Winning Stratagems (勝戰計, Shèng zhàn jì)

- Chapter 2: Enemy Dealing Stratagems (敵戰計, Dí zhàn jì)

- Chapter 3: Offensive Stratagems (攻戰計, Gōng zhàn jì)

- Chapter 4: Melee Stratagems (混戰計, Hùnzhàn jì)

- Chapter 5: Combined Stratagems (並戰計, Bìng zhàn jì)

- Chapter 6: Defeat Stratagems (敗戰計, Bài zhàn jì)

In the first chapter, the author recommends six stratagems, such as killing with a borrowed knife, waiting at ease for a worn-out enemy, looting a house when it’s on fire, and making a feint to the east, but hitting out in the west.

The stratagem of killing with a borrowed knife sounds like a ploy to cover one’s tracks in order to mislead hunters looking for the real perpetrator. However, the true meaning of this stratagem is to attack your enemy by using the forces or strength of a third party or to entice your ally into attacking your enemy instead of doing it yourself.

Meanwhile, the stratagem of looting a house when it’s on fire means taking advantage of the chaos when someone’s house is on fire to stealing the valuables. When it is applied in war and other circumstances, it takes on a much broader meaning.

According to this scheme, you should try to annex territory when your enemy’s country is suffering from internal turmoil. You should take its people when it is being invaded by other forces. Finally, when the enemy’s country is beset with both internal and external crises, you should mercilessly attack and destroy it.

In the second chapter, the most eye-catching stratagem is hiding a dagger behind a smile. Smiles are usually friendly, charming and disarming as well. So, it could also be deadly if someone follows this scheme and hides a lethal weapon behind a smile.

To defeat your enemy with a fatal strike, you need to get very close, and smiles could help you get there. Charming and ingratiating smiles can relax your enemy’s vigilance if not even win his full trust. When your enemy is fooled enough by your smile to let you get close to him, you produce the hidden weapon and slay him in a surprise attack.

Another popular stratagem is contained in the fourth chapter, namely, fishing in turbid waters. This ruse means literally muddying the water so the fish will get disoriented and become easier to catch.

In a chaotic and confusing situation, this ploy could help to win over uncommitted forces involved in the conflict.

When an army panics, officers and soldiers will become disconcerted and divided. They look at each other in an attempt to sense the thought behind the face; they wink to someone or whisper into the ear of the one next to them. They begin to believe in rumors and disobey or ignore orders.

This is an indication of confusion and fear. But this is also the optimal time to persuade them to become an ally and to further press your advantage.

The last stratagem provided by the author in the last chapter of the book advises people to retreat when everything fails. In the face of an overwhelmingly powerful enemy and seeing no chance to win the battle, to retreat is usually the best choice.

Surrender may represent a complete defeat; a compromise may mean a partial defeat; but to retreat is no defeat. As long as you are not defeated, you still retain a chance for victory in the future. This is the so-called “retreat-in-order-to-advance” principle.