Admiral Zheng He (1371-1433) was an outstanding politician and world-renowned navigator. With an aim to establish and develop friendly ties and economic and cultural exchange between China and overseas countries, Zheng He led 100 vessels and more than 27,000 officials and soldiers to visit more than 30 countries and regions in Southeast Asia, South Asia, West Asia, and East Africa through seven trips in a period of 28 years between 1405 to 1433 under the orders of Emperor Yongle during the Ming Dynasty (Yongle was on the throne from 1403-1424).

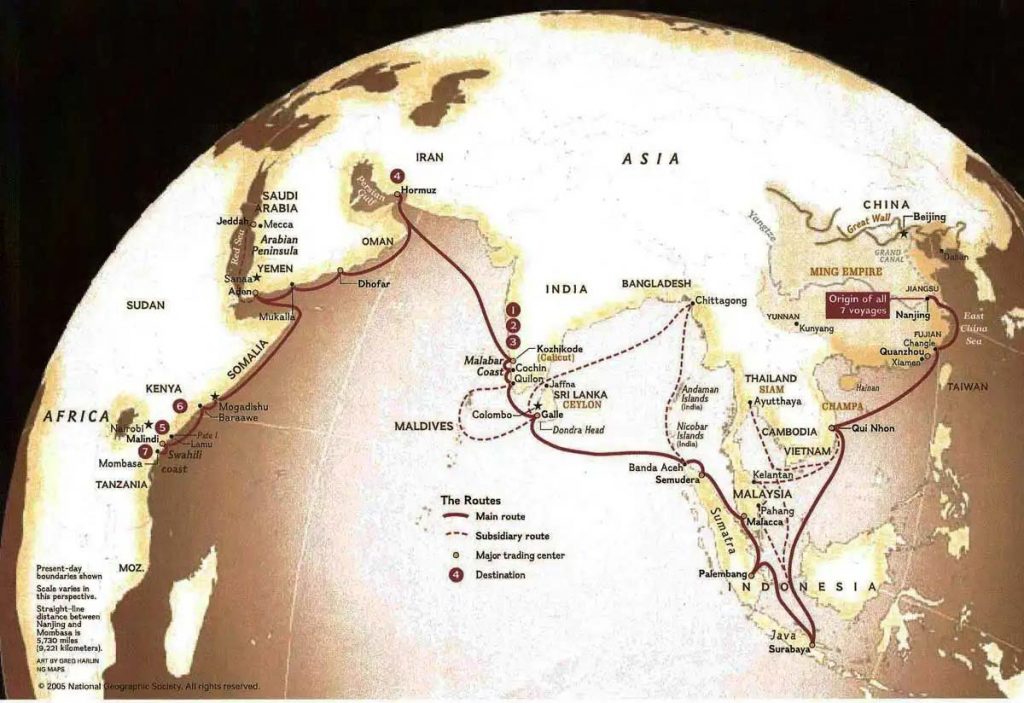

The fleet departed from Nanjing, the capital of the Ming Dynasty. It launched from the Liujiagang Port in Suzhou, sailed past the South China Sea, the Strait of Malacca, the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and reached coasts in East Africa. All told, it navigated 160,000 sea miles. Zheng He defeated risks associated with sailing in his era with exquisite navigation skills. He is regarded as one of the 30 most influential explorers of the past 1,000 years.

The seven voyages of Zheng He

In 1405, the 34-year-old Zheng He confidently accepted an order from Emperor Yongle and started the arduous task of traveling to the western oceans with a fleet as a chief imperial envoy.

Under his leadership, the fleet was active in Southeast Asia, South Asia, and East Africa. According to Zheng He’s strategy, the fleet navigated westward step by step in a ladder shape in line with a “three-layered” structure – taking Southeast Asia as the base, the Indian South Peninsula and coastal countries as the center, and navigating to West Asia and East Africa. With an aim to establish a solid base in Southeast Asia, Zheng He’s first, second, and third voyages focused on Southeast Asia, and the end goal was reaching Guli in South Asia. In the fourth and fifth voyages, the endpoint was moved westward to Hormuz in West Asia. In the sixth and seventh voyages, the destination was pushed to Malindi, Kenya in East Africa. Zheng He, with his excellent command ability and outstanding diplomatic and military wisdom, successfully organized and accomplished these difficult ocean voyages.

A great number of sailors and a complete organization

To fulfill the diplomatic mission entrusted by Emperor Yongle, combat the terrifying waves in the ocean, and deal with any possible military action, Zheng He organized the largest fleet of ships the world had ever seen.

Zheng’s fleet consisted of up to 30,000 sailors. Historical data shows that there were over 27,800 sailors in his first expedition, around 27,000 in the third, 27,670 in the fourth, and 27,550 in the seventh. The number of sailors in the rest of his seven expeditions was not clearly recorded but estimated to be about 27,000, equaling the combined number of the naval armies of the five “Weis” (a Wei was a type of military unit with 5,600sailors) in the early Ming Dynasty.

The fleet included five sub-organizations based on different tasks:

1. Decision-making by fleet heads

The decision-making body consisted of an envoy eunuch and vice-envoy eunuchs of lower positions, who were all ministers of Emperor Yongle and heads of the fleet. As the imperial envoy, Zheng He was the top leader and commander of the fleet. His major assistants included Wang Jinghong, Hou Xian, Li Xing, Hong Bao, and Yang Qing.

The work was executed by such technical personnel as “Huozhang”, “Duogong”, “Bandingshou”, “Tiemao”, “munian”, “dacai”, “shuishou”, “minshao”, “yinyangguan” and “yinyangsheng”. The “Huozhang” equaled present-day captains; “Duogong” took charge of steering based on the captain’s directions; “Bandingshou” were responsible for anchoring; “Tiemao”, “munian” and “dacai” were arranged for all sorts of iron and wood handiwork on board; “Shuishou” and “minshao” were in charge of the sails, oars, and other daily chores; and “yinyangguan” and “yinyangsheng” were those who studied and forecast weather conditions.

3. Foreign trade

The business was handled by officials from “Honglusi, 鸿胪寺” (an organization in the Ming Dynasty established to organize receptions and rituals) as well as compradors and interpreters. The officials from “Honglusi” were responsible for such diplomatic events as banquets; compradors purchased commodities and interpreters were arranged for language interpretation.

4. Logistics

The work was done by personnel from the Imperial Board of Finance like “Langzhong”, “Sheren”, “Shusuanshou” and medical officials. “Langzhong” took charge of money and the supply of materials; “Sheren” drafted letters and files; “Shusuanshou” resembled present-day accountants and cashiers, and medical officials treated diseases.

5. Military convoys

The convoy team was composed of armed personnel at various levels including a general commander, commanders, “Qianhu”, “Baihu”, “Qixiao”, “Yongshi”, “Lishi” and “Junshi”. They were responsible for the safety of navigation, and defense against enemies and pirates.

The complete organization of the fleet ensured the successful accomplishment of every task of the voyage and, at the same time, demonstrated the rich experience of ancient Chinese in ocean navigation.

Huge vessels and diverse categories

Zheng He’s various expeditions involved over 200 vessels of different sizes, which indeed constituted a task fleet of fine structure and complete categories.

The fleet included five types of ships: Treasure ships, horse ships, grain ships, sitting ships, and battleships.

- Treasure ship: It was huge with nine masts and 12 sails. The biggest treasure ship was 114m long and 46m wide, which truly was a masterpiece created by the ship makers. China’s ship-making sector during the Ming Dynasty was a wonder in the history of wooden sailing ships, reached a peak in ship-making by the 19th century, and demonstrated the amazing wisdom and talent of the Chinese people in ship-making.

- Horse ship: With eight masts, it was used for both battles and transport.

- Grain ship: With seven masts, it was designed for grain storage and material supply.

- Sitting ship: It was also called “battle-sitting ship. ”With six masts, it was a place for sailors to rest and camp.

- Battleship: With five masts, it was a fast-speed ship for convoys and battles.

In addition, there were also ships to carry a water supply.

Strict formation and easy communications

1. Big ships and small ships:

Based on different tasks, the fleet formation could be divided into a “big ship fleet” and a “small ship fleet.” The former was responsible for the whole fleet’s major tasks, and the latter was in charge of some temporary jobs. The two fleets could work together or separately, accomplishing diverse tasks flexibly.

2. Formation

The fleet marched forward in an arrowhead-like formation. The core ships, consisting of the ships with “Shuai” – character flags and treasure ships, were in the center of the fleet, a safe position from where to issue orders and commands. Surrounded by battleships on every side, the fleet could rapidly change its formation and defend against enemies effectively in case any part was attacked. The horse ships, grain ships, and sitting ships that were designed to carry sailors and goods were arranged inside the four sides of the fleet and were protected by battleships.

The fleet had a convenient communications system to ensure the orderly formation and effective dispatching. Flags served as means of communication in the daytime. Every ship was equipped with one big “sitting flag”, one signal strip, 10 mast flags, and 50 square-shaped flags. Messages were sent by hanging or waving flags and strips of different colors. Lanterns were used at night, and sound signals would be adopted if bad weather caused poor visibility. Each ship carried gongs and drums of different sizes, which could be used to boost morale in battle and send messages as well. With these convenient communication methods, issuing orders such as marching forward or backward, dining, resting, assembling, anchoring, sailing, or turning around was made possible.

Zheng’s fleet inherited and carried forward the traditional Chinese techniques of navigating using sails. Monsoons from Southeast Asia, the Northern Indian Ocean, and the Arabian Sea regions were the major forces that drove ships forward. As many as 12 sails were used at one time in the large nine-mast ships to maximize the force of the wind. Zheng’s fleet further developed wind-driven nautical techniques and could make full use of the wind from all sides. It was those mature techniques that ensured the safe voyage of the fleet in the vast ocean.

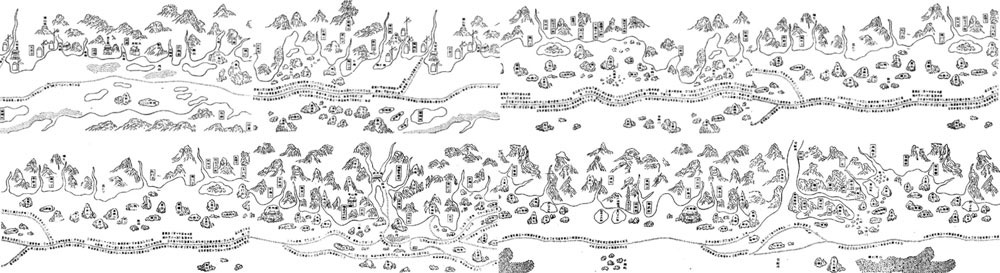

Navigation maps were one of the most basic and necessary tools for navigation, especially ocean expeditions. The Map of Zheng He’s Navigation was the earliest picture used for ocean navigation in Chinese history. It has been passed down to this today. It covered a wide area, had long navigation courses and recorded numerous names of places. Based on traditional Chinese painting methods, the map, with a scroll roll, stretched out from right to left. It vividly shows dozens of routes that started from the Nanjing Treasure Ship Workshop, through the estuary of the Yangtze River to Fujian and Guangdong along China’s southwestern coastline via the Indo-China peninsula. The routes extended westward to the Indian Ocean through the Malacca Strait and further to the Arabian Sea and Arabian Peninsula via the Indian Peninsula, and finally ended in the 10-plus routes along the coast of East Africa. Geographically speaking, the map covered a total area that spans from 44 to 122 degrees east longitude and from 32 degrees north latitude to 8 degrees south latitude. The water area included the West Pacific Ocean and the North Indian Ocean. And the land area spread from Southeast Asia to East Africa and includes the names of 540 places. The painting of the map was the result of the application of a combination of multiple nautical techniques like compass navigation, celestial navigation, object navigation, terrestrial navigation and standard navigation speed.

Zheng’s fleet ingeniously shaped a full set of celestial navigation techniques by combining traditional Chinese astronomical observation and the “Stellar Technique for Ocean Navigation.” When sailing in the ocean, the fleet could be guided by observing coastal objects, the heavenly bodies, and the compass. If no objects on land were visible, observation of the sun, the stars, and the compass were the basic means of navigation. The “Stellar Technique for Ocean Navigation” served as a method to locate where the ship was in latitude by studying the elevation of the stars in the sky. When using this technique, Zheng’s fleet observed more stars that were usually involved in both south-north and east-west directions for verification. Those Chinese navigation techniques were far more advanced than those adopted by other countries in the world.

In this technique, fixed objects on land were used for reference to determine the direction and distance of the trip. It was mainly adopted in offshore voyages. Based on nautical experience, the navigators reminded by surrounding objects could have a clear picture of the location of potential obstacles, peaks, islands, shoals, reefs, and narrow watercourses, as well as the depth of water, the symbols of ports and the correct direction. Zheng’s fleet also employed other techniques in actual voyages like measuring the depth of water through plumb bobs.

The nautical techniques used by Zheng’s fleet were first-class. They helped create the brilliance of the expedition. Regretfully, Zheng’s voyages to the Western Ocean haven’t been appropriately studied by historians. Most works on world history don’t mention Zheng He’s seven expeditions or their geographical discoveries. That is quite unfair. Despite the bigger influence of the great geographical discoveries on world history, the nautical techniques Zheng’s fleet employed went far beyond those adopted by European navigators, and so did the nautical accomplishments it achieved.